Melvine Ouyo, Clinic Director at Family Health Options Kenya

Lisa Shannon

What is the Global Gag Rule?

The Global Gag Rule is one of the most deeply damaging policies ever enacted on foreign assistance funding. When it’s in place, as it has been under every Republican president since 1984, the Global Gag Rule blocks U.S. foreign aid for non-governmental organizations overseas that provide abortion services, counsel patients on abortion, refer patients to other providers for abortion counseling or services, or advocate to decriminalize abortion in their own countries—even if they do these activities with their own non-U.S. funding.

This forces global health providers into an impossible choice:

- They can either forfeit U.S. aid in order to continue providing patients with comprehensive reproductive health services — a decision that is devastating to clinics in resource-scarce settings that depend heavily on U.S. support. Whenever the Global Gag Rule is in place, clinics around the world that reject its requirements have to lay off staff, offer fewer services and reduced hours, and sometimes even close.

- Or, they can agree to the stipulations of the Global Gag Rule in order to continue receiving U.S. funding, forcing them to cease the activities listed above. Doing so impinges on their free speech and unfairly affects patients who don’t receive the comprehensive reproductive health services they need and deserve.

Donald Trump reimposed his expanded version of the Global Gag Rule on January 24, 2025, just days after his inauguration, to coincide with the annual “March for Life” in Washington, DC. The Global Gag Rule does anything but protect life, however. When people can’t get contraceptive services because their local clinic has closed or no longer has a steady supply of contraceptive methods, their risk of unintended pregnancy increases, which leads to more unwanted births, unsafe abortions, and maternal and infant deaths.

Melvine Ouyo, a former nurse at the Kibera clinic and a graduate of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, has seen the effects of the Global Gag Rule firsthand.

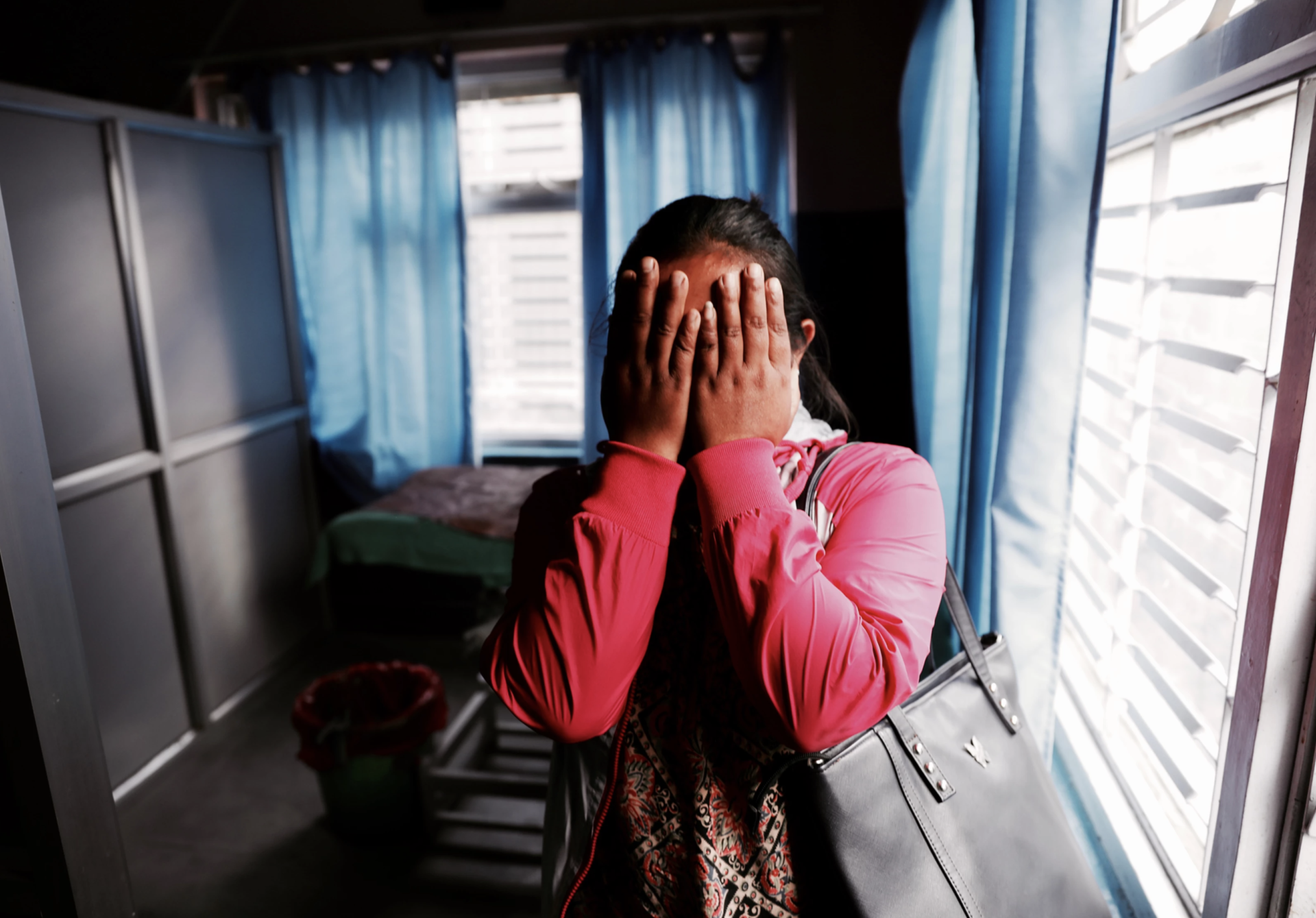

Especially when [patients] are bleeding, we refer them to other clinics for access to the theater or manual vacuum services. Clients will always tell you it was spontaneous. Others will have induced because they didn’t want to carry the pregnancy. Some will come asking for safe abortion service. We always want to help all the women who come to us. We normally take them through counseling: the pros and cons of safe abortion services. We do not offer safe abortion services here, so we link them once they’ve been through counseling and are unwilling to carry the pregnancy to term.

The clinic often sees clients who are desperately ill from an unsafe abortion gone wrong.

They are given herbs. Some of the herbs are actually inserted. Some have come to explain that they have even [inserted] Coca-Cola. There was actually a girl who was given herbs, inserted vaginally, then she inserted a needle. She started bleeding. The bleeding continued, she was feeling faint. Then she was rushed to the facility. Because I was not able to perform a manual vacuum aspiration—I didn’t have the equipment—I referred the client to the Nairobi West facility—it saved her life.

Having family planning in Kibera has helped women to not get pregnant, which has really impacted on the maternal mortality that is a result of unsafe abortion. So really, cutting on family planning would be injustice to the women.

How can we end the Global Gag Rule forever?

The Global Gag Rule is cruel and devastating and must be permanently repealed. The only way to end Trump’s current iteration of the policy and ensure that the Global Gag Rule never returns is through permanent, legislative repeal. The Global HER Act, a bill in both houses of Congress, would prevent a future president from unilaterally reinstating the policy. Please contact your members of Congress and urge them to support the Global HER Act now!

Download a short fact sheet about the Global Gag Rule to print and/or share!

Kenya

Family Health Options Kenya (FHOK) provided 3 million services to women and young people in some of the poorest and most vulnerable parts of the country in 2016 alone. Since 2009, the more than 12 million services FHOK provided helped reduce unmet need for contraceptives in the country, from 26 percent to 18 percent. As a result, the nation’s maternal mortality rate fell too. Abortion was recently made legal in more situations in Kenya, and FHOK is unwilling to deny accurate and complete information to the people it serves. As a result of the Global Gag Rule, FHOK lost $2.2 million in U.S. aid. The organization was forced to close three clinics (in Mombasa, Kitengela, and Isiolo), terminate mobile outreach services that reached 76,000 people annually, lay off 15 staff members, and drastically reduce the number of staffers in its Kibera clinic.

Another organization in Kenya, the Kisumu Medical and Education Trust, provides health care and education to poor women in the country’s third largest city. It expected to receive about $2 million in grants between 2017 and 2021 (more than half its total budget). Because of the Global Gag Rule, it received nothing. The organization was founded by a nurse after she discovered that half of the women in her gynecological ward were there “because of the damage done by backstreet abortions.”

Providing counsel on safe, legal abortion is a critical part of the Trust’s mission to improve women’s health and lives. In order to stay open, the Trust has had to charge for contraceptives that were previously free—a cost that many of Kenya’s poor families are unable to bear. The result is as predictable as it is appalling: reduced contraceptive access and increased unintended pregnancy, unsafe abortion, and maternal mortality.

Colombia

Profamilia has provided millions of vulnerable people medical checkups, critical reproductive health services, affordable contraceptives, health education, and gender-based violence programs since 1964. Colombia still faces numerous reproductive health challenges: Nearly 20 percent of girls ages 15–19 are either pregnant or are already mothers, and rural girls are 26.7 times more likely to become adolescent parents. Illegal abortion remains stunningly prevalent, with at least 400,000 procedures performed each year.

During Trump’s first term in office, the Global Gag Rule ended funding for Profamilia’s program to reduce maternal mortality, its Zika prevention effort, and its outreach to conflict-afflicted communities. Young people in rural areas lost their only access to information and care, undermining the progress made in recent years. The organization was forced to close four of its clinics, which had served 60,000 people.

Niger

Niger has one of the most rapidly growing populations in the world. Between 1960 and today, it has grown from 3.5 million people to more than 21 million, and is likely to nearly triple by 2050. Half the population is under 15 years old, and more than 40 percent of its people earn less than $1 per day. Levels of contraceptive use are low, and women have a 1-in-23 chance of dying of pregnancy-related causes. By any measure, Niger is teetering on the edge of catastrophe. Marie Stopes International (MSI) began providing contraceptives and reproductive health care through mobile outreach in 2014, and opened its first clinic in 2016, with support from the U.S. government. That year alone, MSI served some 30,000 clients and provided contraceptives to more than 16,000 women and girls, preventing thousands of unsafe abortions. But, because MSI provides safe abortion in other countries, where it’s legal, the Global Gag Rule disqualified the agency from further support for its crucial work.

Nepal

The maternal mortality rate in Nepal used to be the highest in the world, and the abortion law was, until recently, the most restrictive in the world. Women who had abortions—and survived—were routinely sentenced to long prison terms. In one infamous case, a 13-year-old girl was raped by a relative and made pregnant. Another relative took her for an illegal abortion. Yet another relative reported her to the authorities, and she was sentenced to 20 years in prison. When Nepal changed its abortion law in 2002, the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN)—unwilling to deny women information about safe, legal abortion—immediately lost American funding for family planning services and contraceptive supplies. As a result, 60 health workers were laid off, mobile reproductive health clinics were eliminated, and the agency’s ability to provide access to a regular supply of birth control withered. After President Obama lifted the Global Gag Rule in 2009 and FPAN had its funding restored, Nepal’s maternal mortality rate fell by a third. That progress was disrupted under Trump’s first imposition of the Global Gag Rule.

Zambia

The Planned Parenthood Association of Zambia (PPAZ) lost half of its annual operating budget in 2017. It had to close all but three of 16 sites working to provide HIV testing and treatment to residents of rural areas. PPAZ’s staffing has been decimated. One remaining center, in Nyangwena, serves 3,000 people over an enormous rural area, but has just two community workers delivering HIV care and one overseeing tuberculosis (TB) cases. Outreach efforts were eliminated, the number of people being tested for HIV and other STIs plummeted, and teen pregnancies increased. PPAZ’s program to offer in-home testing, distribute contraceptives within communities, and offer family planning information in schools was ended.

Stories from the frontlines

Kenya

Family Health Options Kenya (FHOK) is one of the leading providers of reproductive health services in the country. For over fifty years, they have provided their clients with comprehensive care. FHOK refused to sign Trump’s Global Gag Rule because they will not deny their clients’ access to the full range of medically accurate information. Subsequently, they lost their U.S. funding, forcing them to shutter the doors of clinics serving Kenya’s most vulnerable communities.

Kenya Patient and Provider StoriesNepal

The Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN), a member association of the International Planned Parenthood Federation, is Nepal’s first national sexual and reproductive health service delivery and advocacy organization. FPAN works across 37 districts to provide critical health services to poor, marginalized, socially excluded, and underserved communities. As an organization that believes access to comprehensive reproductive healthcare is a human right, FPAN refused to sign Trump’s Global Gag Rule.

Nepal Patient StoriesNigeria

Education as a Vaccine works in Nigeria to apply youth-friendly approaches to improve the health and development of children, adolescents, and young people. Ipas Nigeria works to increase access to vital reproductive health care and strengthen alliances and partnerships in support of sexual and reproductive health and rights. Both organizations refused to sign the Global Gag Rule.

Nigeria Organization Stories