Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN)

The Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN), a member association of the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), is Nepal’s first national sexual and reproductive health service delivery and advocacy organization. FPAN works across 37 districts to provide critical health services to poor, marginalized, socially excluded, and underserved communities. As an organization that believes access to comprehensive reproductive healthcare is a human right, FPAN refused to sign Trump’s Global Gag Rule.

Stores below collected by Lisa Shannon, Cofounder and CEO of Every Woman Treaty

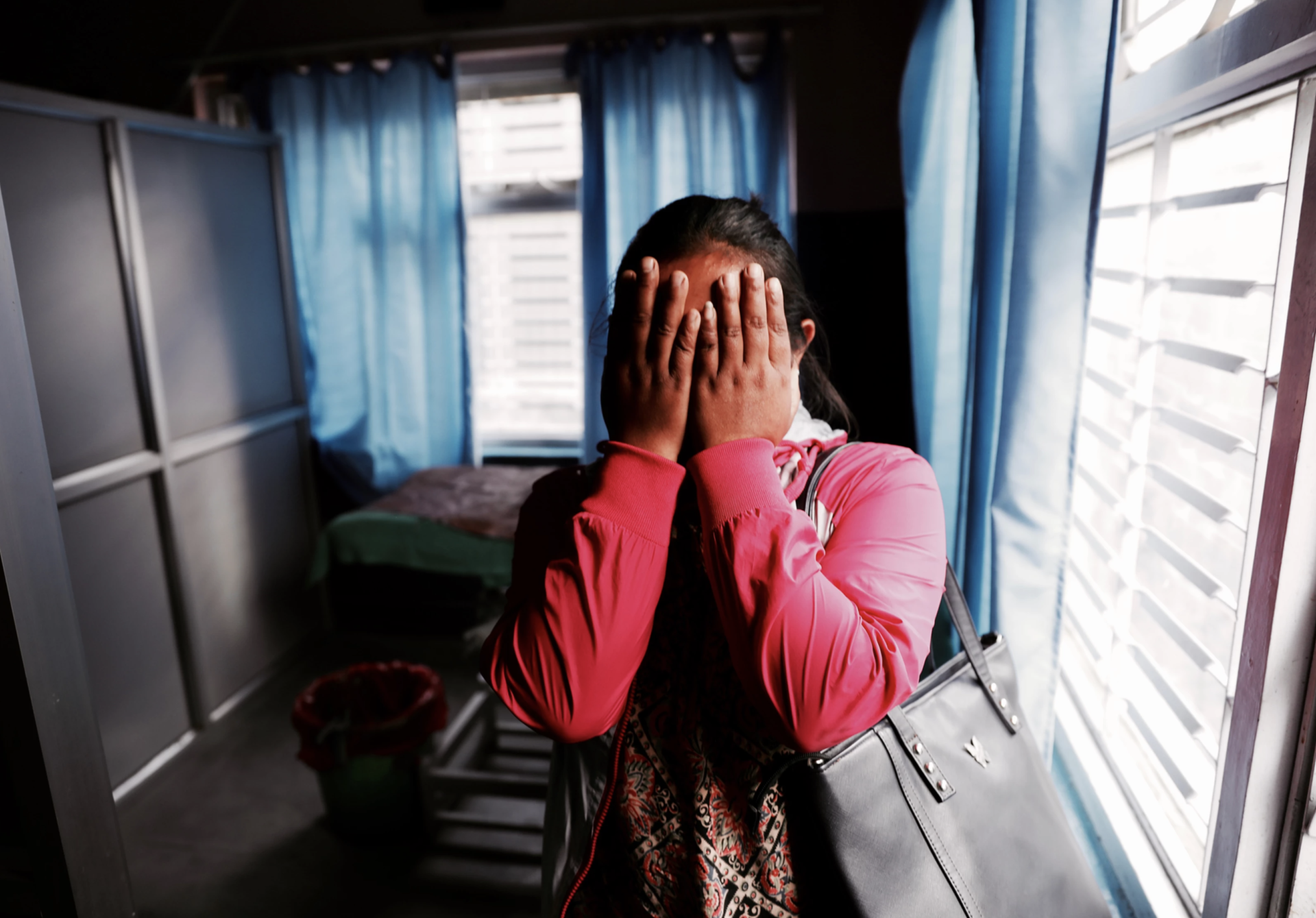

Binsa*

“If I had a boyfriend, my husband would kill me,” Binsa says with a nervous laugh, by way of clarifying it was her husband who impregnated her. We are tucked away in a quiet office, three stories up in a suburb of Kathmandu, looking over a mish-mash of rooftops and clotheslines. Binsa has come here to the FPAN Valley Clinic for a safe abortion. She’s accompanied by her younger sister.

She’s had a lot of health issues, yes, and already has a nine-year-old daughter. But that’s not why she’s opted for an abortion. It is because her husband has tried to kill her, choking her when in fits of rage. She attributes this violence to tradition in her Tamung ethnic group, where, she says, “Drinks and fighting are normal.” The fighting in her home includes “very physical violence. Because of that, I left the country.”

Last year, Binsa sent her daughter to live with her sister, and took work in a garment factory in Jordan. The days weren’t too long: eight or nine hours, plus Fridays off. But it was dusty and smokey. She was supposed to be gone a year, but she got sick. Some problem with her thyroid, the feeling her whole body was burning. “I ended up spending all my money on health care.”

So she came home. When Binsa told her husband she missed her period a couple of months after returning from Jordan, he began probing her: Why did you come back so fast? All your friends are still over there. Who’s to say it’s my baby. I can’t be responsible… “My husband did not support having another baby. Raising a child is hard, especially with no job.”In fact, Binsa’s husband pushed for her to abort that pregnancy. Today, Binsa and her husband keep all their finances separate. “Even though we have a child, he is not supportive. He says I have to raise the child on my own.” This time, urges for an abortion have been replaced with death threats. “I will kill you. I will kill your daughter.”

“I just want to go away.” Even though the marriage was arranged, Binsa states firmly she cannot leave and bring shame on the family. I turn to her sister, and ask, “Surely you would support your sister leaving this man. The situation is very serious. She could die. Your parents would get that, right?” The sister says yes. But Binsa just shakes her head, “My sister is in the same situation.”

*Binsa is a pseudonym to protect the person’s identity.

Tika* & Unat*

Tika and her husband Unnat arrive at the FPAN clinic on a motorcycle, dusty from the road. They married 12 years ago, when she was 18 and her husband was 20. They have two children: an 11-year-old daughter and a six-year-old son. They have come to FPAN for a vasectomy, to cap their family at the two children.

Why? “Happy family,” Tika shares in English. A peaceful family with the means to send both of their children to school. It’s a decision they arrived at together, and later informed his elderly father who lives with them. A vasectomy, specifically, because it is a less invasive procedure than tubal ligation for her.

Unnat adds, “I must say this is a very important service for rural villages. More so than the city. It is easier for city people to get access to contraceptives. They can just pay for it.”

*Tika and Unnat are pseudonyms to protect the people’s identities.

Devna* & Sejun*

Devna and Sejun have come to the FPAN Central Clinic for a medical abortion. They have been married for 13 years, and have two sons, ages 11 and three. They use condoms for birth control. This pregnancy happened accidentally.

Devna and Sejun explain that it is already very difficult to make ends meet, so the decision to limit their family to two children is firmly rooted in survival economics. “We don’t have a house. Life is expensive. We have to educate our children. So we came here.”

They came to FPAN after hearing about the safe, affordable services through a friend. “Before, we didn’t know it was legal to terminate a pregnancy.” When asked if they made the decision together, they both nod emphatically in agreement, holding hands.

After the procedure, Devna smiles and says it went well. As she sits on the edge of an exam table, pulls down her sleeve, and FPAN staff give her a shot of Depo-Provera, an injectable contraceptive that is effective for three months.

*Devna and Sejun are pseudonyms to protect the people’s identities.

Alisha* & Bibek*

Alisha and Bibek have been married for 12 years, and together for 15. Before they married, they talked about family planning, and decided two children—only two children—would be “God’s gift.”

Today, they have a 10-year-old daughter, and a seven-year-old son. Both are in school.

Alisha used Depo-Provera injectable contraceptives for many years, but developed health problems. “She wasn’t doing well. So, we thought: Vasectomy. It will be safe.”

“Before, people were illiterate. In villages, people had eight children, 12 children. Now, the government is doing promotions to have two children, three children. To have a better education. We agree with it.”

*Alisha and Bibek are pseudonyms to protect the people’s identities.